A free market isn’t the same as “freedom.” In several blog

posts,

I’ve heavily criticized the conservative perspective that naively – and inaccurately

– couples neoliberal economics with our broader concept of freedom.

Like economist Milton Friedman and his legion of followers, proponents

of free markets argue that any governmental regulation that prevents a private

enterprise from achieving its profit goals is a widespread and unlawful attack

on the freedom of every man, woman, and child. On the surface, the logic of the

argument is convincing. Government regulation – in the form of new environmental

standards, stricter health standards or small business registration hurdles –

creates costs for private companies. It inhibits people’s ability to start new businesses

that create jobs and to generate profits, which presumably create more jobs.

But the connection between free markets and freedom is more

complicated than that. It originates in the two socio-economic systems that at

one time characterized our way of life on this planet. Up until the 1990s,

“free-market” capitalism was considered the opposite of Soviet-style communism,

in which economies were centrally planned, consumer choice was non-existent,

and citizens were subject to the whims of a few centralized authorities. This

dichotomy between

communism

and capitalism was characterized in the West as “The Free World” vs. “Behind

the Iron Curtain.”

I recently came across an

interesting

article in

Salon.com that articulated

the irony of our perception that free market capitalism equates to freedom in

society. In particular, author Sara Robinson argues that neoliberal economics

is not a counter to Soviet-style communism but in fact analogous to its attack

on individual liberties. There are at

least three ways in which the free market ideology now mimics Soviet-based

communism.

Central Planning and

Control

First, one of the things we associate with communism is

central planning and control of the economic system. The supposed free market

approach was meant to completely decentralize economic development through the “invisible

hand.” (The invisible hand theory argues that, driven by self-interest,

individuals will use capital to address market needs, creating value for both consumers

and themselves.)

But a small number of business leaders today possess shocking

levels of power over society. As Ira Jackson from the Kennedy School at Harvard

explained, CEOs and executives of companies are “the new high priests, reining

oligarchs of our capitalist system.” Driven primarily by the need to create

shareholder wealth, these individuals secure highly prestigious positions of

influence over governmental bodies. They do so through mechanisms like the US-based

“super PACs” – powerful

political action committees

that spend millions of dollars bolstering, but not directly supporting,

political candidates or specific pieces of legislation. They wield power through

the “

revolving

door syndrome” – a practice that sees people from an industry take

regulatory or legislative jobs overseeing that industry, and vice versa. And

these powerful business leaders also suffer from the assumption that they are “

too big to fail”.

Consider JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon, who

sits

on the board of the Federal Reserve, the very same body meant to regulate

his firm. Consider the many food and beverage corporations that have immense

influence on food and safety regulations. Or the

cozy

relationship between oil giants and the Minerals Management Service – a

now-defunct federal regulatory body that was responsible for managing the

United States’ natural gas, oil and other mineral resources. That relationship resulted

in the approval of careless oil projects and was associated with

serious

oil spills.

It is in business’ best interest to replace government

regulation with self-regulation. And when that happens, you get CEOs and top

executives - not that unlike communist totalitarians - with substantial power over the very products and services that

define our way of life.

Limited Consumer

Choice

Second, communism limits consumers’ choice to those products

and services determined by the state, not the market. Ironically, though,

consumer choice in the West has become severely limited under free market

capitalism.

My students often argue it is the consumer’s responsibility

to “vote with their dollars”: the free market provides a powerful force through

which to address issues of inequality and sustainability. I cringe when I hear

this argument, though, because it overlooks the fundamental motivation of

business: to limit consumers’ choice of products and services by erecting entry

barriers to new ones or by buying out and eliminating existing ones.

For instance, North American consumers today have no choice

but to purchase appliances that will break down in approximately seven years.

This unavailability of longer-lasting appliances is not caused by limited technological

capabilities; it is the result of an optimality equation designed to maximize

repeat revenue. Companies make more money if they can sell you a new stove

every seven years rather than every 30. Gone are the days, as Robinson

explains, when products are as abundant as the mom and pop shops that sourced

them. Product diversity is the antithesis of economies of scale and if

companies have the power to limit the supply of this diversity, they will. So,

the supposed freedom associated with market demand for products and services

has been severely stunted by companies’ quest for market dominance and power.

The Propaganda Machine

Third, and perhaps most sinister, is the level of cognitive

influence companies hold over us. During the Cold War, the

Iron Curtain earned its

name because of its ability to prevent citizens living behind the curtain from

knowing what was happening outside the borders of their country. This information

control kept citizens in check and ensured the outside world didn’t affect people’s

acceptance of the communist regime.

It’s no coincidence that one of the largest expense items on

a corporation’s balance sheet today is communications, marketing and public

relations. It is absolutely mind-boggling to comprehend the sheer magnitude of capital

used by corporations on communications to the public. I’ve

said

before that it’s hard to believe this marketing hasn’t had a substantial

impact on our values, our beliefs, and our way of life. As Naomi Klein

explained in her book No Logo, marketing has evolved from promoting a product

to promoting a lifestyle. As the largest institution in today’s society,

business’ impact has gone beyond the provision of a product or service to the

primary vehicle shaping society.

A very important debate I have with my students is whether

citizens of the West realize how much the plethora of marketing messages dominate

their lives. My students have a difficult time accepting the notion that their

behaviour is influenced by decades of messaging. In their minds, every consumer

has the ability to detach from this external influence and make objective

decisions. But this assumption overlooks the fact that business, like any other

actor, has the ability to socially construct the norms and beliefs of a given

society, whether intentionally or not.

Take, as an extreme example, a marketing initiative that introduced

the scent of bacon into baby blankets to establish a solid future customer

base. On top of all this, there’s the very monopolistic media industry, where

the dissemination of information is based on whether it generates shareholder

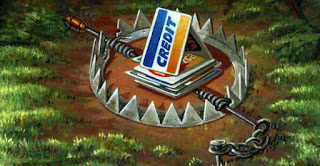

return rather than whether it in the best interests of society. There is no question in my mind that the West

is equally trapped behind an iron curtain of commercialization, excessive

consumption, and a biased media, shielded by a seemingly endless supply of

messages.

Where is the freedom that a “free market” society was

supposed to provide?

Stephen Barley, one of the most prominent management

academics recently called on his fellow researchers to examine more closely the

influence companies have on those institutions meant to protect democracy and

the public good. He did so in the backdrop of the role creditors played in changing

bankruptcy reform, which made it more difficult for individuals to declare

bankruptcy, and the role pharmaceutical companies’ played in persuading the US

congress to amend the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act so that drugs are approved

without going through any clinical trials.

Yet management scholars have spent more time examining how

companies can more effectively play this role rather than examining how to

engage in business practices that preserve democracy and the public good. A rather large research area in business is

what is known as Corporate Political Activity where some of the leading

management scholars theorize how for-profit businesses can manipulate the

regulatory environment for their own benefit by, for example, pushing for

government policy that will position firm level capabilities as having a

competitive advantage over competitors.

So while there is no doubt in my mind that “freedom” is a

contentious term when discussed in the context of the “free market”, we as

business scholars are no less complicit than the companies who directly or

indirectly erode such freedoms.

The garment factory collapse in Bangladesh was one of the most tragic industrial catastrophes in recent decades. Over 1100

dead textile workers have been recovered, making it the largest textile

industry tragedy and the second worst industrial disaster after Bhopal where 2,259

people died in 1984. This particular

catastrophe hit home to Canadians because one of our major corporations,

Loblaw, sources garments from this factory for their Joe Fresh line.

The garment factory collapse in Bangladesh was one of the most tragic industrial catastrophes in recent decades. Over 1100

dead textile workers have been recovered, making it the largest textile

industry tragedy and the second worst industrial disaster after Bhopal where 2,259

people died in 1984. This particular

catastrophe hit home to Canadians because one of our major corporations,

Loblaw, sources garments from this factory for their Joe Fresh line.  The public’s response to the tragedy is one

of shock and horror, with many consumers pleading ignorance that they were

completely unaware of the conditions surrounding the making of the very products

they wear. Some have promised

to boycott

the Joe Fresh line to voice their dissatisfaction with the conditions in

Bangladesh. Perhaps not surprisingly, the general public has a short

memory when it comes to the working conditions of those manufacturing their

garments. Issues of unfair and unsafe

working conditions in Asia have been around for decades with Nike taking a

brunt of the blame back in the 1990s when they were boycotted for purchasing

from suppliers employing children and paying workers below living wage.

The public’s response to the tragedy is one

of shock and horror, with many consumers pleading ignorance that they were

completely unaware of the conditions surrounding the making of the very products

they wear. Some have promised

to boycott

the Joe Fresh line to voice their dissatisfaction with the conditions in

Bangladesh. Perhaps not surprisingly, the general public has a short

memory when it comes to the working conditions of those manufacturing their

garments. Issues of unfair and unsafe

working conditions in Asia have been around for decades with Nike taking a

brunt of the blame back in the 1990s when they were boycotted for purchasing

from suppliers employing children and paying workers below living wage.